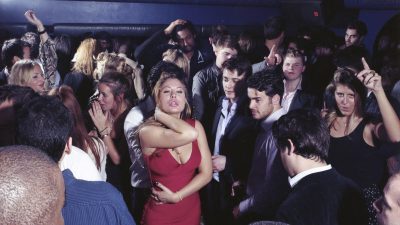

Zed Nelson – Gun Nation

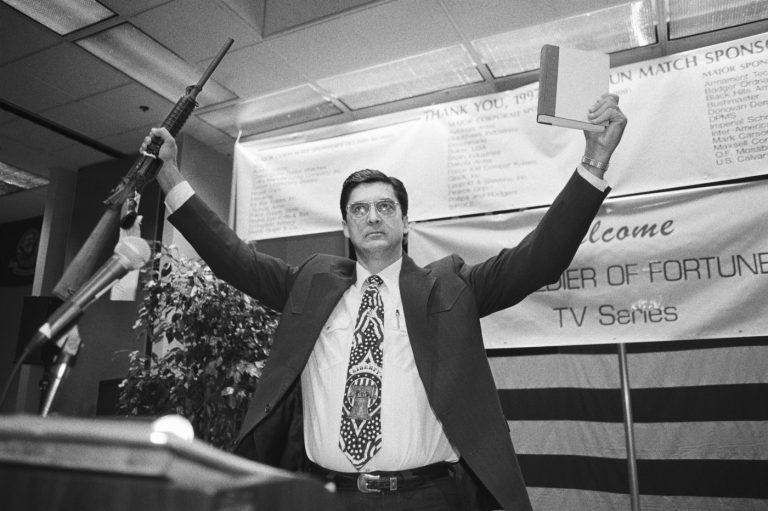

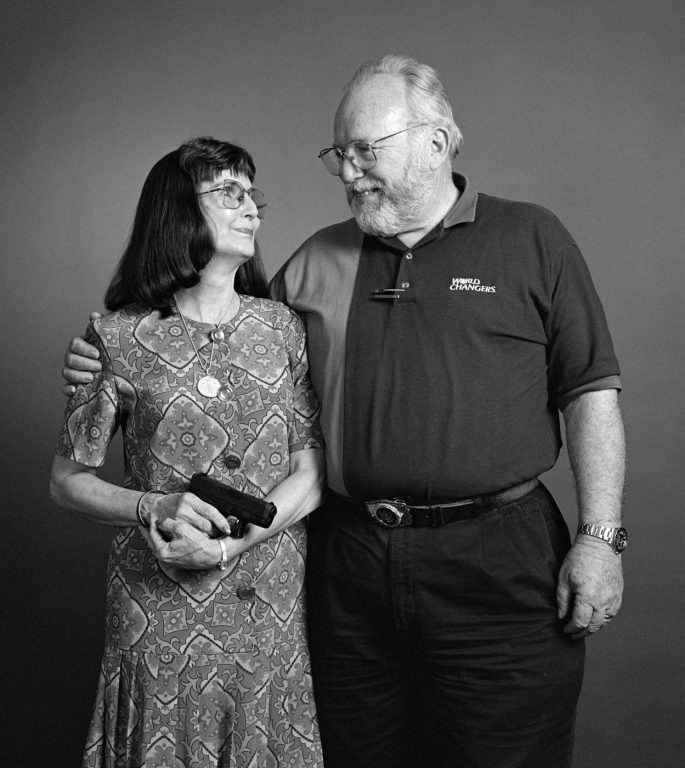

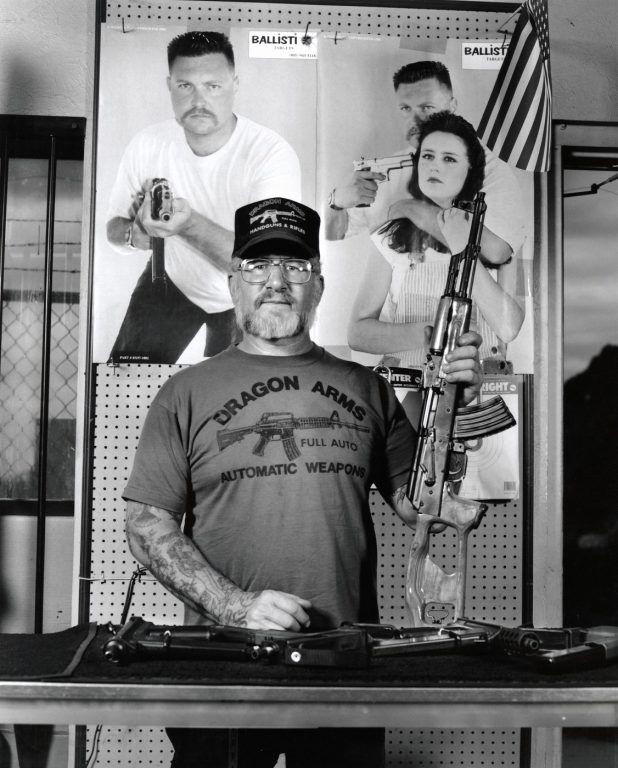

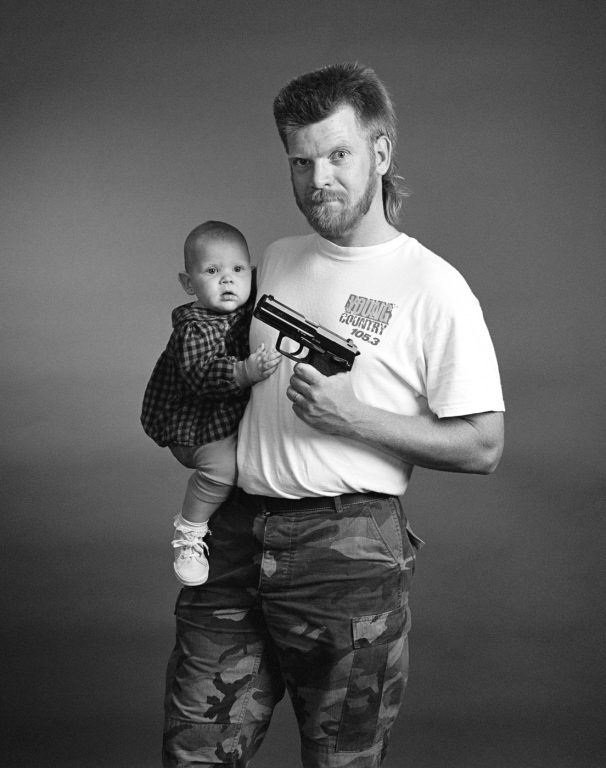

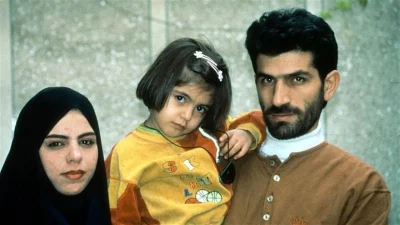

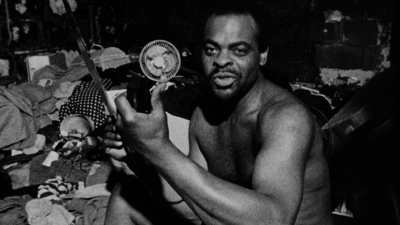

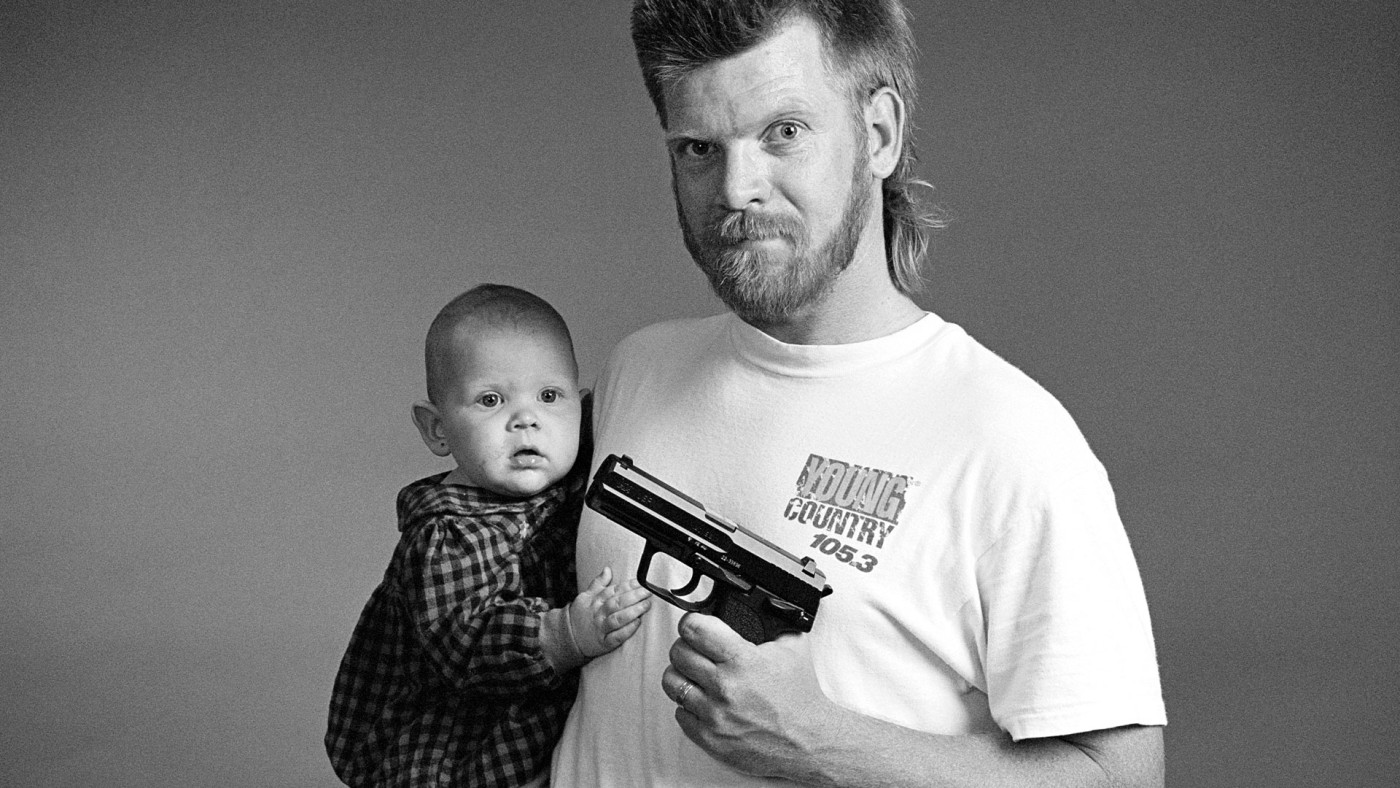

Gun Nation is a moving and provocative collection of portraits of gun owners and gun culture created in the immediate aftermath of the Columbine massacre.

2016, somewhere in the American West. Zed Nelson has been challenged by a gun-owner to join her on a shooting expedition somewhere out in the wilderness. When you are photographing people it happens quite often, he explains. ‘If you want to inhabit their world people like to lay down a gauntlet and test you out.’ So, after a lengthy drive into the mountains, the group’s pair of 4×4 vehicles stop and their small crew of gun aficionados unload their enormous cache of high powered hunting weaponry, arranging it carefully on the ground. Targets are erected and turns are taken to unload live rounds. It is eventually Zed’s turn to pick up one of these killing machines and put it to use. The experience, he recalls, was both terrifying and exhilarating: ‘I have this rather pathetic, male, childish fixation with [guns]… my parents banned me from having toy guns so I made them myself out of wood and nails’. And it turns out that the subsequent two decades spent wielding a camera – sometimes even in war zones – prepared him perfectly for the occasion. ‘It turns out that I’m a brilliant shot. I think it was because of film making and photography, because you learn to not shake and hold something steadily’. For the first time during his fascinating and lengthy conversation with MadeGood, Nelson wavers slightly and loses his train of thought. Gun sights and the photo lens never seemed closer. It’s an uncanny sensation audiences of his work will be familiar with; a sense of witnessing yourself appear and then disappear inside the troubled, compromised worlds he has shot.

On this occasion he was shooting a short film follow up film to the seminal 1999 photography book Gun Nation; a moving and provocative collection of portraits of gun owners and gun culture created in the immediate aftermath of the Columbine massacre. Nelson returned to the same locations 17 years later to meet his original subjects again, to try and understand why his subjects remained so committed to their weapons and so impervious to calls for greater control and regulation, in the context of a seemingly never ending cycle of mass shootings. His companion on this occasion was a woman in her 40s. On camera she possesses an icy, intelligent gaze, which wavers only slightly when recalling her first meeting with Zed. ‘17 years ago when we last met I think it ended it tears for me, because I realised again what I would do if they came to take my guns. That would be the end of it for this country for sure and I’m not willing to hand that over… I know I’m able to do it and I know I would do it’.

Nelson responds, ‘What is “it”?’

‘Protect my rights’ she says. ‘The rights of my friends. The rights of my loved ones. The rights of this country.’

‘You mean armed struggle?’

‘I think so. I wouldn’t let it go easily.’

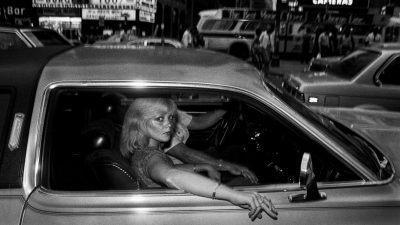

In the relaxed confines of his East London home, Nelson describes himself as a journalist looking for simple stories, but who in doing so has been drawn into increasingly complex, disturbing worlds. The wide ranging interview is never more fascinating than when he describes the subtle arts of documentary photography: how to overcome the deep suspicion American gun owners have of liberal/left wing media types, and get them to sit for a portrait. How overhearing hipster conversations in Hackney coffee shops inspired a best-selling book of portraits. How he turned an arduous schedule of mainstream magazine commissions into a ground-breaking book on the global beauty industry. The film is a treasure trove of inspiration for budding documentarians, and an insight into how a long career as a professional artist, that started with typical earnest naivety, can evolve into a complex and culturally significant body of work.

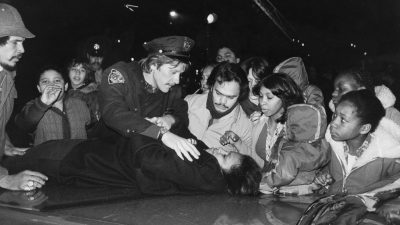

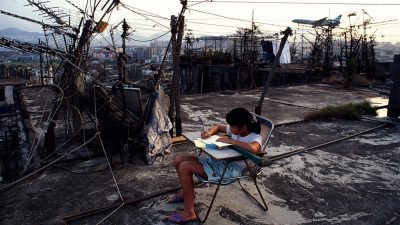

More than anything Nelson’s reflections suggest a blueprint for bringing grown-up, politicised and empathetic yet sharp and uncluttered artistic material into life. A career journey that took in a terrifying armed ambush in Afghanistan gradually evolved into a calm, insightful world view with a distaste for the corrupting influence of violence and money. It’s a compelling journey. ‘This grew out of ten years of work on other subjects. I couldn’t have done [Gun Nation] if I hadn’t done all the preceding work, which was documentary reportage around the world, going to war zones, going to Somalia and Afghanistan, Angola. I slowly realised that all the weapons being used in these wars were made in the our home countries in the West, and I became more and more increasingly frustrated by seeing that, and realising that those weapons hadn’t just been bought, they’d often been donated by our governments’. As witness to a globalised economy of violence, Nelson began to see American domestic gun violence as a component of this. The number of deaths per year can only be compared to outright warfare: Nelson quotes a figure of half a million, between the two instalments of Gun Nation, which is near enough correct. The five worst mass shootings in American history have all taken place between 1999 and 2016. In the same period precisely 213,169 died as the result of intentional assault with a gun while 360,433 were suicide. Today, 73% of all homicides are gun related in the US, compared to just 3% in the UK and 38% in Canada. Nelson’s intimate, provocative photographs in the 1999 book captured an epidemic in its earliest stages. It’s hard to fathom how 17 years later American gun culture had utterly failed to correct. This is what drew Nelson back, to track down his original subjects and try and understand how so little had changed.

It has been clear for some time that the American gun cult is underpinned by an axis of the National Rifle Association, the gun industry and the conservative mass media, articulated through a latent and deeply ingrained conservative/libertarian/evangelical Christian ideology (while Nelson never crosses into this territory, it is quite clearly adjacent to white supremacism as well). Allusions to the mythos of the western frontier abound. ‘I was really interested in how the icon of the gun had been sold’ says Nelson. ‘It’s been sold as an American ideal, as an icon of freedom and independence. And that is how the advertising industry as far back as the wild west has packaged and sold guns. They made up a myth… they built a whole culture around guns that [is] deeply embedded.’ It is certainly clear form the film that gun cultists believe themselves to be protagonists in an existential struggle for survival, encircled by “bad guys”, liberals and government. With their fears marshalled by the NRA and Fox News, they represent a formidable bulwark to rational, compassionate efforts to reduce bloodshed.

Anyone who pays any attention to sensible coverage of American gun violence knows all of this, but given the impasse there is a particular value in Nelson’s humane, considered and largely unjudgmental documentary approach. When faced with the force of marketing, ideology and myth ‘you have to counteract that with the same degree of skills and enthusiasm’, and, I would add, with the same ability to tell a powerful story.