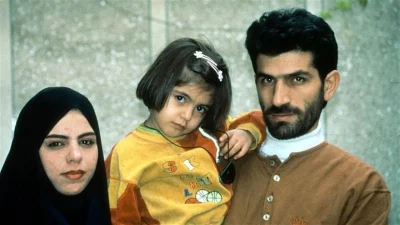

Midnight Family

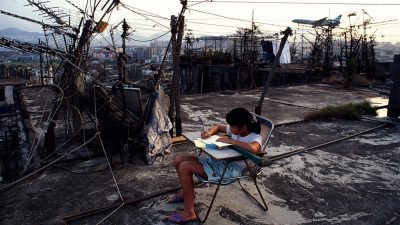

In Mexico City’s wealthiest neighborhoods, the Ochoa family runs a private ambulance, competing with other for-profit EMTs for patients in need of urgent help. As they try to make a living in this cutthroat industry, the Ochoas struggle to keep their financial needs from compromising the people in their care.

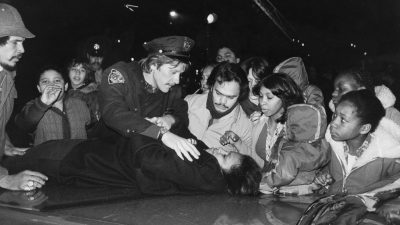

In Mexico City, the government operates fewer than 45 emergency ambulances for a population of 9 million. This has spawned an underground industry of for-profit ambulances, which are often run by people with little or no training or certification.

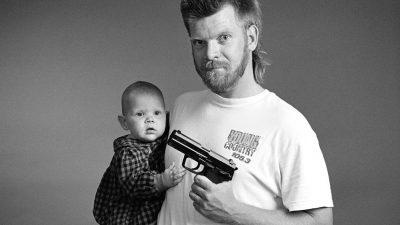

Midnight Family is the story of the Ochoa family, who started an unlicensed EMT business in the late ‘90s after buying a retired ambulance from Oklahoma. Using their network of police contacts, the Ochoas pay a 300 peso (17 USD) bribe for every accident call sent directly their way. When lucky enough to arrive first to the scene, they charge patients 3800 pesos (185 USD) for transport to a hospital. For the past 20 years, this lively and likable family has just been able to make ends meet in this line of work.

Unlike many competing ambulance operators who push ethical limits much too far – extorting helpless patients or refusing to transport people in critical condition who don’t have means to pay – the Ochoas have tended to be a trustworthy exception within this fraught industry. As desperate patients wait for hours when government ambulances are nowhere to be found, the Ochoas arrive quickly, filling serious medical needs. They charge only when patients can reasonably afford the costs and spend much of their time supporting people who would otherwise be left without any care at all.

Our story unfolds as the status quo of the Ochoas’ business is jeopardized by increased local police vigilance. Although some private EMTs do engage in illegal and abusive practices, the cops frequently target private operators to get bribes rather than to enforce the laws governing independent ambulances. As EMT businesses risk being shut down, the Ochoas must find a way to get enough money to legitimize their ambulance or they too will lose their only means of making a living.

With this increased pressure, it becomes clear that being the warmhearted exception in an illegal and corrupt industry is extremely difficult and complicated. Police officers begin to demand higher bribes, and the Ochoas are increasingly compelled to conduct their business more aggressively and self-servingly, just like everybody else. We follow the Ochoas on a journey filled with ethical dilemmas, as they are forced to choose between the well-being of their patients and the future of their family business.

Midnight Family is a story about doing what you can with what you have. It asks us to consider whether the survival of one’s family legitimizes wrongdoing, particularly in contexts where corruption is the norm. In humanizing one family’s ethically compromised business, the film explores urgent questions around healthcare, the failings of government and the complexity of personal responsibility.

Directors Notes

I moved to Mexico City in December of 2015 and lived around the corner from the General Hospital. Every day, I walked past hundreds of desperate people waiting outside the gate of the overburdened facility, and I slowly grew curious about the state of medical services in a city of 9 million. Though I hadn’t come to Mexico to focus on healthcare—I was there to develop an entirely different film—it was impossible to ignore the sheer force of the emotions I encountered on my daily commute. Without knowing exactly what to look for, I began to explore.

I knew I had found a story worth telling after meeting the Ochoa family. One afternoon, sixteen-year-old Juan was cleaning their ambulance outside the General Hospital as his 9-year- old brother, Josué, clumsily juggled a soccer ball. Intrigued by the idea of a family-run ambulance, I asked them if I could ride along for a few hours. Fer, the father, was quick to agree. What I experienced that night was jaw-dropping—a film waiting to be made.

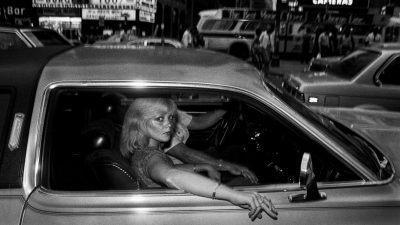

Over the next six months, I lived in the back of the Ochoas’ ambulance, filming, with gut- wrenching access, Mexico City’s cutthroat underworld of for-profit healthcare. As I soon discovered, this industry was new not only to me but to locals as well. I spoke with politicians, taco stand owners, families and students; almost nobody knew where their ambulances came from or what sort of EMTs were behind the wheel.

The Ochoas became my close friends. I loved being with them and knew they were good people. And yet the more time I spent in their ambulance, the more I learned about darker details of their operation. I discovered that they were not all certified as EMTs and that their ambulance was unregistered and not fully equipped. While they continued to provide much- needed services to a city lacking sufficient emergency care, I saw their financial insecurity begin to affect their treatment of their patients. My sense of right and wrong in knots, I kept asking myself, “What would I do here? What’s the better alternative?” I rarely had good answers, if any at all. And as their frequent run-ins with bribe-demanding police officers made clear, the Ochoas were operating within an inherently corrupt, dysfunctional system, trying to scrape by like millions of other Mexican families.

As the accidents became more serious and the pressure on the Ochoas intensified, the lines I hoped they wouldn’t cross drew frighteningly close. Though often proud of their work, at other times I worried for the patients in their care. This emotional and ethical confusion became the central tension of my story.

Working as a one-man crew, it took months of trial and error to figure out how best to tell this story. The Ochoas’ repetitive nightly routine let me experiment with different styles of shooting and gave me multiple opportunities to work with the feelings and energy that I was witnessing. I wanted the film to be first and foremost a thrilling experience. With my camera, I hoped to convey the physical and emotional roller coaster I was riding every night. I knew that interviews, music and voiceover could pull the audience out of the ambulance’s world and lead

them to judge the Ochoas’ work from a disconnected perspective. I also knew the questions I wanted to explore were delicate. Viewers would have a spectrum of reactions, and showing the situation instead of telling it would encourage a much richer and more nuanced conversation. Inspired by patiently composed ethnographic works as well as drama-filled narrative films, I felt the Ochoa’s story provided a unique intersection of these two cinematic modes, which are often considered contradictory. My aim was to take an audience on a breathtaking ride while honoring my conviction that long takes and distilled observation could offer a bracing form of realism.