Midwives

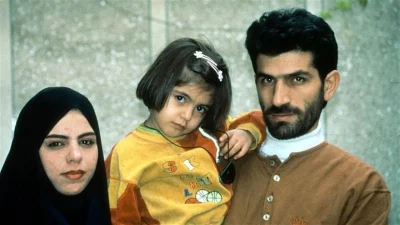

Hla and Nyo Nyo live in a country torn by conflict. Hla is a Buddhist and the owner of a makeshift medical clinic in western Myanmar, where the Rohingya (a Muslim minority community) are persecuted and denied basic rights. Nyo Nyo is a Muslim and an apprentice midwife who acts as an assistant and translator at the clinic. Her family has lived in the area for generations, yet they are still considered intruders. Encouraged and challenged by Hla, who risks her own safety daily by helping Muslim patients, Nyo Nyo is determined to become a steady health care provider for her community. Snow Hnin Ei Hlaing’s remarkable feature debut was filmed over five turbulent years in a country that has long been exoticized and misunderstood. The filmmaker’s gentle, impartial gaze grants unique access to these courageous women who unite to bring forth life. Filled with love, empathy, and hope, Midwives offers a rare insight into the complex reality of Myanmar and its people.

“Without us, where would they go?” asks Hla, the Buddhist founder of an antenatal clinic in a rustic town in western Myanmar. She’s referring to the Muslim – or Rohingya – women that live in the area and who are actively spurned by other similar establishments. In 2016, the Rohingya people, who primarily reside in Rakhine, became the focus of a devastating campaign of ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar military. Tens of thousands have been killed and almost a million fled the country. Snow Hnin Ei Hlaing’s observational documentary Midwives follows the fortunes of Hla’s clinic in Rakhine, and the lives of its founder and her Muslim apprentice, Nyo Nyo.

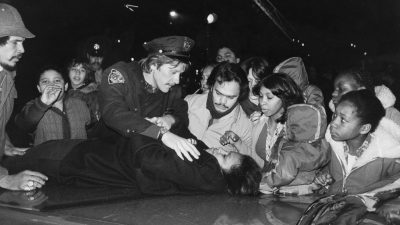

The film’s opening sequence is precisely what we might expect from a documentary about midwifery: a pregnant woman arrives at the clinic, and, after some candid footage of treatment and the averting of potential complications, she gives birth to a healthy baby. However, far from a conventional warts-and-all depiction of a rural medical facility, what Hlaing crafts is a more nuanced portrait in which the clinic acts as a microcosm of contemporary Myanmar, pulling at the threads that weave together the private and the public, the personal and the political.

The most prominent of these threads is the remorseless persecution that has drawn the ire of the international community over the past five years. While the film regularly utilises news footage of chilling anti-Rohingya marches – “Get out! Get out! Terrorist Muslims! We won’t live with them!” – it’s how this dynamic occurs within intimate sections of the populace that is one of the film’s most interesting elements. “We have three Buddhist patients,” explains Hla’s husband; “the rest are ‘them’.” Even for a couple who have risked reputation and livelihood by accepting Muslim women at their clinic, old-fashioned language and perspectives still prevail. Though her affection for Nyo Nyo shines through in various moments, Hla’s response to her apprentice often seems coloured by stereotypical, racially charged assumptions. Hla regularly refers to Nyo Nyo as “kalar”, which translates to ‘darkie’, and which Nyo Nyo hates, as she later confesses to camera.

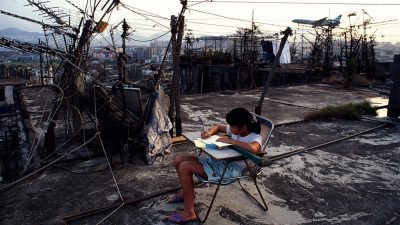

Expanding beyond the two women themselves, Hla speaks openly about the way other members of the town have shunned her and her husband as a result of them treating Muslims. They equally have to be careful not to allow Nyo Nyo ever to care for one of their Buddhist patients. Despite this, when the clinic is temporarily closed down, they help unemployable local Rohingya by supplying them with ice lollies that they can sell in nearby villages. Elsewhere, Nyo Nyo is keen not to let the fact that Rohingya children have been ostracised from schools prevent them from receiving an education, so in her spare time, she ropes her husband into teaching a gaggle of eager kids. In particular, they try to make sure the children can speak the Burmese language rather than just the Chittagonian Bengali dialect that Rohingya typically speak; the language barrier constantly rears its head in the clinic, and Nyo Nyo’s ability to translate makes her additionally valuable to Hla.

The tensions between the women are not always the result of these wider social rifts – Hla chides Nyo Nyo in ways familiar to intergenerational relationships the world over. Hla is something of a potty-mouth and her no-nonsense personality can feel brusque both to friends and patients, but proceedings are also punctuated by flashes of humour. Some of those come as a direct result of unexpectedly robust language – at one point, Hla plunges a spoonful of pink medicine into a baby’s mouth, saying “take this, you little bitch” – while in others, she and Nyo Nyo giggle together as they’re serenaded by a ludicrous local man.

Throughout all of this, it is perhaps the empathy and detail with which Hlaing captures life in Rakhine that makes Midwives so moving. Where newsreels and military officials strain to erase the individual from the homogenous Buddhist and Muslim masses, the film explores the daily trials of real people. Even when Hla and Nyo Nyo’s relationship takes a difficult turn – as when Nyo Nyo decides that she wants to set up her own clinic – the camera remains a confidant and observer with a subtle, sensitive gaze. Rather than allowing them to be defined by their religions, Midwives treats Hla and Nyo Nyo as distinct, complicated, resilient women. In presenting the difficulty of their lives and the ways in which they have defied their situations, it finds hope in even the most adverse of circumstances.